Chipotle, McDonald’s, Starbucks, Jack in the Box and Shake Shack are planning to raise menu prices. Fast-food franchisees are laying off employees or cutting their hours. Smaller independent business owners, meanwhile, worry their workers will bolt unless they also increase wages.

With California’s mandatory minimum wage for fast-food workers set to jump to $20 an hour on Monday, major restaurant chains are scrutinizing every aspect of their businesses to find ways to offset the extra money they will soon be spending on labor. In many cases, customers will end up eating the cost.

“It’s going to be a pretty significant increase to our labor,” Jack Hartung, Chipotle’s chief financial officer, said of the new law during the company’s third-quarter earnings call. He estimated that the burrito chain would boost prices by “a mid-to-high single-digit” percentage as a result. “We are definitely going to pass this on.”

The pay increase established by Assembly Bill 1228 applies to California fast-food workers employed by any chain with more than 60 locations nationwide, and covers corporate-owned and franchised locations. The state has more than 540,000 fast-food workers, about 195,000 of them in Los Angeles and Orange counties, according to the latest May 2022 figures from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The current minimum wage in California, regardless of industry, is $16 an hour, meaning many cashiers, line and prep cooks, counter attendants and baristas will see as much as a 25% raise overnight.

Fast-food workers rally outside a McDonald’s restaurant in Monterey Park last July in a push for better working conditions.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Jaylene Loubet, 25, has worked as a cashier at a McDonald’s in Cypress Park since 2017, initially making $16.25 an hour.

Since then her hourly pay has only risen to $17.50, she said, the same amount that her mother, a longtime cook at the same location, makes. The two live with Loubet’s father in a one-bedroom apartment in Glassell Park, unable to afford a bigger place.

“When you’re in a tough financial situation, even though it’s not enough to be comfortable, it does help,” Loubet said of her upcoming raise. That said, “food is going up as well, rent is going up as well, bills are going up as well. Even with the $20, money is still going to be tight.”

With the federal minimum wage stuck at $7.25 an hour since 2009, many states and cities have taken it upon themselves to lift the pay floor. But the California bump for fast-food workers is unusual for targeting a specific business sector and adjusting the minimum rate by so much at once.

“This is such a dramatic increase on a state minimum wage that was already quite high,” said Harry Holzer, a Georgetown University public policy professor and the Labor Department’s chief economist in the Clinton administration. “The workers who keep their jobs will be happy — they will be better off.”

Less so for consumers of fast food, who will undoubtedly pay more for their burgers, tacos and fried chicken. David Neumark, a minimum-wage expert at UC Irvine, estimated that overall prices will rise between 2.5% and 3.75%.

That’s relatively small, but comes on top of the steep inflation that customers have faced at fast-food establishments in the last few years. Nationally, prices at limited-service restaurants are up almost 30% from February 2020 levels, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And more fast-food price increases will hit lower-income households harder because they spend a larger share of their income on food and consume disproportionately more fast food.

A spokesperson for McDonald’s said the company was exploring several ways to counterbalance the increase in labor costs and has yet to decide how much it will raise the price of menu items. Although McDonald’s provides “informed pricing recommendations,” the spokesperson noted that final pricing is at the discretion of franchisees.

Pedestrians walk by a Starbucks in Hollywood. The coffee chain said it will raise the pay floor for all levels of employees in California to retain workers.

(Wesley Lapointe / Los Angeles Times)

Starbucks said it had elected to raise the pay floor for all levels of employees in California to retain workers and to combat wage compression — when there is little difference in pay between experienced workers and entry-level ones. It plans to offset the increased labor expenditure “through a variety of levers — including near-term pricing as well as other efficiencies,” a spokesperson said.

The economic effects of such a sharp and sudden pay hike are unclear. In general, raising the minimum wage helps large swaths of low-wage workers, bringing some out of poverty, but others will lose out as employers scale back through layoffs, shorter shifts, reduced hiring and other cost-saving measures.

“Where they can automate, they will automate more,” Holzer said. “Maybe some franchises will move out of state.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has already spurred more fast-food operators to install self-service ordering kiosks, and the industry is looking at other ways to depend less on human labor, including the use of robots.

Proponents of the new law say fast-food corporations can afford to pay up. The industry has flourished since the pandemic began as customers sought cheap and quick meals, leading to billions in sales and record profits.

But the brands say they, too, have had to contend with high inflation for ingredients and supplies and have already raised wages for their workers without government prompting. Between 2019 and 2022, the average weekly wage for employees at limited-service restaurants jumped 26% to $501.

Franchise owners in particular are anxious about their ability to shoulder the extra costs; labor accounts for roughly a third of a typical fast-food operator’s expenses.

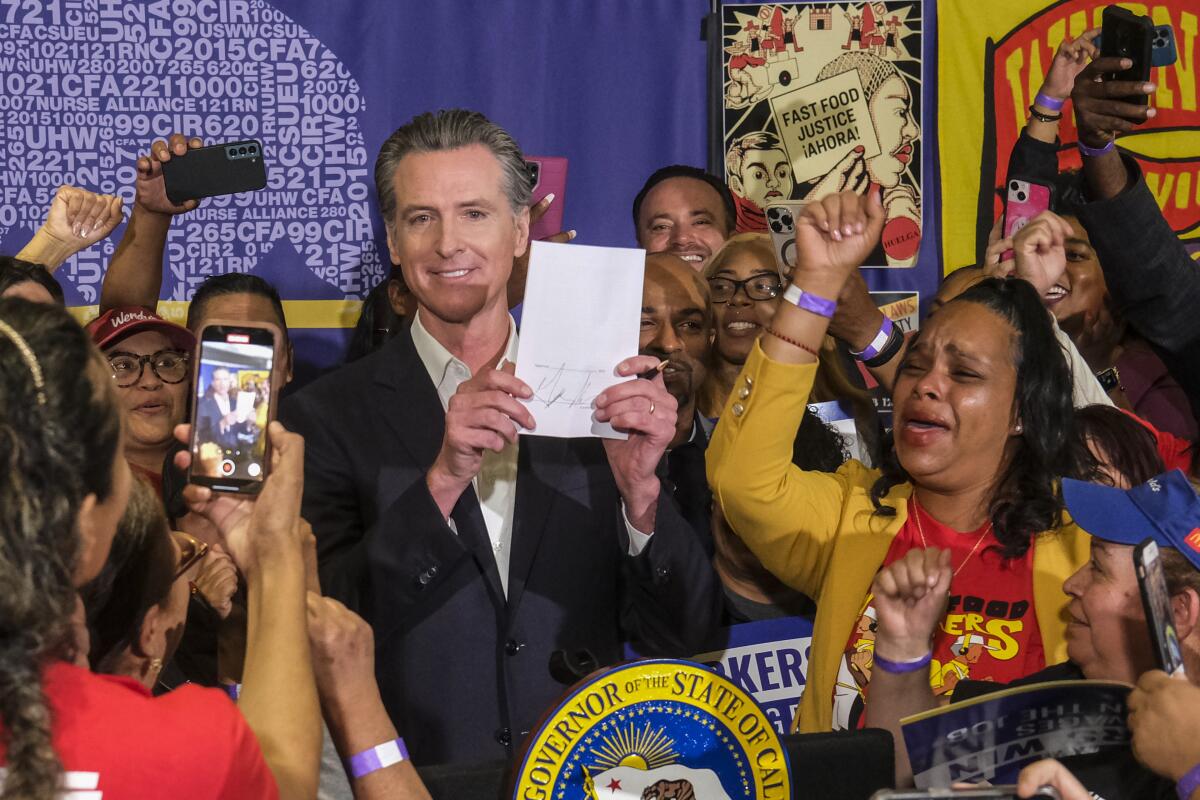

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, surrounded by fast-food workers in Los Angeles, on Sept. 28 signs Assembly Bill 1228, which established the $20 an hour minimum wage at fast-food restaurants.

(Ringo Chiu / Associated Press)

Shortly after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the pay increase legislation into law in September, hundreds of Pizza Hut franchises in California moved to lay off more than 1,100 delivery drivers, federal and state filings show.

The affected Pizza Huts are run by franchise operators and located from Orange to Stanislaus counties, according to the California Employment Development Department. The layoffs were expected to go into effect in February.

Fast food is tightly woven into the history, cultural life and economic growth of Southern California.

Brothers Richard and Maurice McDonald opened a drive-in restaurant in Pasadena in 1937, a few years before starting the first McDonald’s in San Bernardino. Another pioneer, Carl Karcher, bought a hot dog cart in L.A. in 1941 and went on to found Carl’s Jr.

Taco Bell, In-N-Out Burger and Jack in the Box also come from the region.

Collectively, their explosive growth across the U.S. and sustained success over the decades symbolized the busy American life, the rise of the baby boomer generation and California’s love affair with cars.

Yet the industry has come to be seen as the stereotypical low-wage sector where millions of workers make minimum wage and toil under tough and sometimes unsafe conditions, making it a prime subject of the Fight for $15 movement and such books as “Fast Food Nation.”

The passage of AB 1228 represented a significant win for fast-food workers who for years have organized for better wages and protections. Along with the higher minimum, the new law established a Fast Food Council — composed of business and labor representatives — that has the authority to set future pay increases (at a maximum of 3.5% a year) and develop standards on working conditions and employee safety and training.

‘This is such a dramatic increase on a state minimum wage that was already quite high.’

— Harry Holzer, a Georgetown University public policy professor

Employees at fast-food or limited-service restaurants nationwide work about 25 hours a week on average. Many face unpredictable hours with some called in on short notice or required to work split shifts — two separate periods in one day.

Angelica Hernandez, who works as a cook trainer at a McDonald’s in Monterey Park and was appointed to the Fast Food Council, called the $20 minimum wage “good progress.” But she worries that the restaurant will respond by slashing employee hours, which she said it has done in the past after increasing wages.

“They’re utilizing one person to do the job of two, three or four people,” she said.

Angelica Hernandez works as a cook trainer at the McDonald’s in Monterey Park. The minimum-wage increase is “good progress,” she said, but she wants to see more improvements in the industry.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

Earlier this year, workers formed the California Fast Food Workers Union, which is part of the Service Employees International Union, to bargain with the council. The union has said it plans to push for annual wage increases, predictable schedules and just-cause protections.

Workers can expect to maintain some leverage in future negotiations as growth slows. There is still tight competition for fast-food workers, though not as stiff as at the height of the Great Resignation in 2021-22, when many people quit their jobs and rethought their work and life priorities after COVID-19.

A guaranteed $20 an hour could lure people on the sidelines into the fast-food job market, including teenagers who once dominated the fast-food workforce, economists said.

Over the years, the average age of fast-food workers in the U.S. has been rising gradually as many teens have instead sought enrichment jobs to prepare for college. The median age for fast-food workers is now 22.1, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Zev Brown, a senior at Eagle Rock High School, has worked government jobs and on political campaigns since his sophomore year, earning $18 to $25 an hour.

Although he knows classmates who have jobs at Starbucks, McDonald’s and Burger King, he said most of his friends prefer to work for local mom-and-pop businesses or start their own money-making ventures.

“People want to work in the neighborhood they call home and the neighborhood in which they go to school,” Brown said. “Side-hustle culture and entrepreneurial culture are really big.”

That said, $20 an hour makes a fast-food job “more enticing for a student,” said his friend, 17-year-old Sawyer Sariñana, who has been making money through photography work.

“I would definitely consider it now — I think that’s a big jump and makes a big difference,” said Sariñana, also a senior at Eagle Rock High School.

Fast-food locations in grocery stores, airports, hotels, theme parks, sports venues and other businesses are exempt from the minimum-wage increase, as are employers that operate a bakery on the premises — a loophole that has raised questions about whether Panera Bread and others like it must comply.

At first, it might seem that restaurant employers not covered by the mandate now have an advantage: As the big fast-food chains lay off or hire fewer staff, that could expand the pool of available workers — who could be paid less than $20 an hour. But owners of independent fast-casual and full-service restaurants aren’t sure that will be the case, and anticipate having to raise wages to keep pace.

“Every bump in the restaurant labor market raises the prices for everyone, period. It doesn’t leave us out,” said Jeff Strauss, owner of sandwich counter Jeff’s Table in Highland Park.

West Hollywood’s and Seattle’s experiences with rapidly increasing their minimum wages provide a look at how things might go in California after the April 1 wage hike kicks in.

West Hollywood raised its minimum wage to $19.08 an hour in July after vehement opposition from business owners, and just days before chef Josiah Citrin opened his steakhouse and seafood restaurant Charcoal Sunset.

Over the next several months, Citrin said he did everything he could to make it work, including cutting his staff from 50 employees to 30 and rolling out a more limited menu.

‘At a point, you can’t trim anymore. When I closed at the end, there was no more money to operate.’

— Chef-owner Josiah Citrin, who closed Charcoal Sunset shortly after West Hollywood increased its minimum wage to $19.08 an hour

But the high wages and a severe pullback in customer spending due to the Hollywood strikes were too much for the fledgling restaurant to overcome. Citrin closed Charcoal Sunset in February.

“At a point, you can’t trim anymore,” he said. “When I closed at the end, there was no more money to operate.”

Seattle, one of the first in the national Fight for $15 campaign, lifted its minimum wage from $9.47 an hour in April 2015 to $13 in January 2016 — a 37% jump over a nine-month period.

Researchers at the University of Washington found that businesses overwhelmingly survived, said Jacob Vigdor, a University of Washington public policy professor who directed the minimum-wage study.

But overall employment at eating and drinking establishments in Seattle grew at a notably slower pace after 2016, and there was another downside: Employees saw fewer hours of work — on average by about 10%.

In 2017, Seattle made it more costly for restaurant and retail employers to send workers home early and make other scheduling changes. Labor union officials in California are hoping to do the same at fast-food restaurants.

“It was never just about wages,” said April Verrett, the SEIU’s national secretary-treasurer. “This is about empowering workers.”

Times staff writer Suhauna Hussain contributed to this report.